Modernity and Domesticity

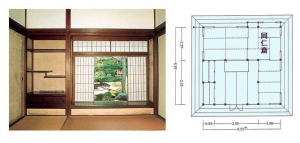

Fig1 Syoin Dukuri

Kyoto Jishouji Toukyudou Doujinsai 1485

(Photo from http://blog-

imgs-45.fc2.com/k/a/s/kashiwada758/blog_import_4c861244d4b87.jpg)

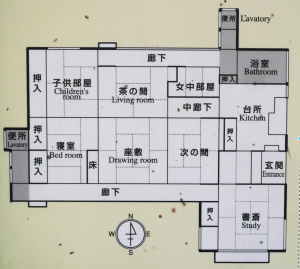

Fig2 Takeo Kobayashu

New house design competition 1st place

1920s

(photos from author)

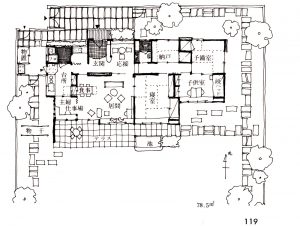

Fig3 Yutaro Shibuya Jyutaku Kairyokai

Competition Honarable mention

1933

(figure from the book by

Kiyoshi Hirai)

Fig4 Masako Hayashi, Syouji Hayashi

Our House (Watashitachi no Ie)

Tokyo 1955

(Photo from author)

Fig5 Kazuo Shinohara

House in White

(Shiro no Ie)

Tokyo 1966

(Photo from Koji Taki)

Fig6 Toyoo Ito

Mikimoto

Tokyo 2006

(Photo from author)

1.Improvement in women’s social status and patriarchy

In Japan, how did these concepts develop and affect architecture? In Japan, unlike Europe, domesticity was not firmly established during the 19th century. The first half of the century belonged to the Edo period[1], when Japan was a feudalistic state and patriarchy was firmly embedded in the society. The country opened its doors to the outside world in 1868 and Meiji era started. Majority of the homes belonged to the middle class, which had a guestroom for the head of a family in the center, emulating the patriarchal design of a samurai warrior’s residence (shoin dukuri – see figure 1).

A typical example is the house of Soseki Natsume, one of the most famous novelists in Japan’s literary history (fig. 2). In this house, the entrance is directly connected to a study for the head of the family (a remnant of shoin – a master’s study) on the left, and to a waiting room and a drawing room to receive guests to the front. This type of a house, which is built around a reception area for the head of a family, was slowly replaced by more family oriented house that has a living room in the center, in the 1920s. (Seizou Uchida et. al, Pictorial of Modern History of Japanese Houses, Kajima Press, 2001) [1] 1603 – 1867

In 1916, Jyutaku Kairyoukai (Society for Home Improvement) was established, which held a design competition as a part of its activities in search of new type of residence that takes gender equality into consideration (fig. 3). One of the designs that received an honorable mention at the competition shows that a housewife’s work areas are located in a preferred side of the house, that is, the south side facing the garden. On the other hand, a reception area is placed right next to the entrance, facing north[2]

2.Avant-garde and domesticity in modernism architecture

In Japan, houses that placed domesticity at the core of the design started to be built around the 1920s, when modernity was leading the collapse of traditional domesticity in modernism-centered Europe. It was triggered by the critiques for the traditional house design, which was influenced by the information belatedly imported from Europe. Simultaneously, information on modernism architecture was also brought in. In Europe, domesticity established in the 19th century was torn apart by the modernity of the 20th century. In Japan, as the concepts of domesticity and modernity were introduced almost at the same time, there was little time lapse between a birth of design that combined modernity and domesticity, and that of avant-garde design that put much emphasis on modernity. Many of representative architects for the former were from Tokyo University of the Arts, including Jyunzo Yoshimura (1907 – 1997), Mayumi Miyawaki (1936 – 1998), and Yoshihiro Masuko (1940 – ), together with Taro Amano (1918 – 1990) and Masako Hayashi (1928 – 2001). Architects belong to the latter group are represented by the school of Kazuo Shinohara (1925 – 2006), including Toyoo Itoh (1941 – ).A representative work by Masako Hayashi is called “Our House (fig. 4)”. It demonstrates warm domesticity by placing a living room in the center of the house, which is surrounded by a dining room and other rooms. On the other hand, a representative work by Kazuo Shinohara called “House in White (fig. 5)” features a living room that creates a strong impression with its high ceiling and white walls, isolating itself from other rooms in the house. Its artistic appeal implies a denial of a traditional idea of a family home. In the mid-20th century Japan, two types of modernity – masculine modernity and feminine modernity – were simultaneously displayed in residential house designs.

3. Avant-garde and kawaiiWhen

Toyoo Itoh, a Shinohara-school architect, was designing a house in Nakano-Honcho for his sister, he was aggressively pursuing the avant-garde style of Kazuo Shinohara, his mentor. Later, around the time when he designed “Silver Hut” in 1986, his style began to change to give greater considerations to the inhabitants’ domestic activities than the modernity, bringing the former to the front and taking the latter to the back, and held back artistic statements by the architect. It doesn’t mean, however, that he returned to modern domesticity explained above. In fact, what he did was to invert the key traits of modernism architecture – simplicity, integrity and authenticity – to bring vagueness, softness, and cuteness (kawaii) to the front. Many Japanese architects in the early 21st century followed his style. Tomoharu Makabe, an architecture critic, called it a “kawaii architecture (cute architecture)” and summarized its key characteristics as follows:

Not complete but incomplete irregularity

Likable, sense of security

Smallness, stupidity, imbalance, diversity

Source: Investigation on designs in kawaii architecture paradigm, Heibon-sha, 2009

According to Makabe, the “kawaii architecture” has been developed along with the changes in Japanese social structure, from patriarchic to matriarchic. During the ultra-high economic growth era after World War II, Japanese fathers spent long hours in the office and came home very late, only to sleep. Meanwhile, the role of a head of a family has been gradually transferred to mothers, and the bond within maternal line has been enhanced.

In Japan, unlike Western Europe , domesticity – femininity – was not established in the design of residential houses in the 19th century. The idea was imported, almost simultaneously, with the concept of modernity – masculinity – in the 20th century, and both were embraced by different schools of architects and realized in physical architecture. In fact, the both schools pursued modernism architecture. Therefore, in the 20th century Japan, two types of residential designs, modern domesticity – femininity, and modern avant-garde – masculinity, co-existed. As Makabe pointed out, new architecture, developed as a reaction to the modern avant-garde architecture, has become a part of “kawaiiarchitecture” – femininity – in the 21st century. In today’s Japan, this feminine architectural style is getting attentions of the society.

[1] 1603 – 1867

[2] In Japan, the south side has always been preferred, as it gets a lot of sunshine. The north is considered a taboo in Buddhism.